Perhaps the greatest and most prolific Scottish myth of all can be found where it’s least expected: in the beloved system of clan tartans.

The earliest example of tartan found in Scotland dates to the third century and was used as a stopper in an earthenware pot found on St Kilda. Known as the Falkirk tartan, it’s a simple two coloured check, the undyed brown and white wool of the Soay sheep.

In A Journey From Edinburgh Through Parts of North Britain, Alexander Campbell recorded a description of the Scots from a writer of the latter end of the sixteenth century:

“They delight in marled clothes, especially that have long stripes of sundry colours, they love chiefly purple and blue. Their predecessors used short mantles or plaids of diverse colours sundry ways divided, and the custom is observed to this day, but for the most part they are now brown, most near to the colour of the heather, to the effect when they lie amongst the heather the bright colour of their plaids shall not betray them. The plaid is worn only by the men, and it is made of fine wool. It consists of diverse colours, and there is great ingenuity required in sorting the colours so as to be agreeable to the nicest fancy.”

In 1703, Martin Martin, in A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland, gives the first account of the use of tartan as a means of identification. He noted that the colours and patterns of tartans could be used to differentiate between the inhabitants of the different regions of Scotland.

“Every isle differs from each other in their fancy of making plaids as to the stripes in breadth and colour. This humour is as different through the mainland of the Highlands, in so far that they who have seen those places are able at first view of a man’s plaid to guess the place of his residence.”

Each community in Scotland would have had at least one weaver, and they would produce tartan cloth to supply to people in the local area. The colours of these ‘district tartans’, as they have come to be known, would have been determined by the plants that grew in the area that could be used for dyeing cloth, making each tartan distinct from the others. This geographical system of identification was the only one that tartan was part of at the time; it would be another hundred and fifty years before the concept of clan tartans was introduced. Even the use of the word tartan in reference to a checked cloth is not recorded until the Dress Act of 1746, which refers to “tartan or party-coloured plaid of stuff“.

The Dress Act of 1746 prohibited the wearing of any tartan, with the exception of the military tartan of the Black Watch, which could still be worn by members of the regiment. The Dress Act was a knee-jerk reaction by the government to the Jacobite uprising, part of a series of measures attempting to bring the Jacobite clans under government control. A later amendment to the act revised it to forbid the wearing of tartan “west and north of the Highland Line”, a perceived division between the cultures of the Gaelic Highlands and the Scots Lowlands that ran from around Dumbarton in the west to Perth in the east.

Just south of that boundary, a firm of weavers, William Wilson and Sons of Bannockburn, cornered the market for supplying tartan to the military and the increasing number of Highland regiments. By the time the tartan ban was repealed in 1782, Wilson and Sons were thriving. The company sent out agents to the Highlands to meet clan chiefs and authorities, and they returned with various samples of cloth from the district weavers. Wilson’s Key Pattern Book of 1819 documented weaving instructions for over two hundred tartans, many of which were renamed by Wilson in an attempt to match clans or towns to tartans, in addition to some rather fanciful titles deriving from the colours in the tartans, like the ‘Robin Hood tartan’.

The repeal of the Dress Act in 1782 saw a huge surge in Scottish nationalism and the advent of the era of Highland Romanticism, helped along by the works of Robert Burns, James McPherson, and Sir Walter Scott. Highland Societies sprang up all over Britain, promoting ‘the general use of the ancient Highland dress‘ and required their members to wear it to attend Society meetings. The idea that a clan name should be connected to a tartan was catching on, and in 1815 the Highland Society of London wrote to clan chiefs to request that they provide the Society with samples of ‘their clan’s tartan’. Many chiefs had no idea what their clan tartan was supposed to be, so they, in turn, wrote to tartan weavers like Wilson’s to seek advice on the matter. One querent, in a letter from Wilson’s archives, asks “Please send me a piece of Rose tartan, and if there isn’t one, please send me a different pattern and call it Rose.”

In 1822, tartan’s popularity soared almost overnight when King George IV became the first reigning monarch to visit Scotland in one hundred and seventy-one years. The visit was organised by Sir Walter Scott, who had convinced the King that he was a direct descendent of the House of Stuart, as Bonnie Prince Charlie had been. Scott subsequently persuaded the King to don the full Highland dress for his visit and the King duly agreed, spending over £100,000 on a bright red tartan outfit complete with solid gold accents, a sword, and pistols. A grand ball was held, with Scott demanding that everyone attend “all plaided and plumed in their tartan array“. Scott’s pantomime of pageantry was a great success, and firmly lodged the idea that tartan was Scotland’s historic national dress in the minds of the people.

Following the royal visit, several books documenting tartans were published, which only served to add fuel to the fire. Amongst these books was the first collection dedicated to clan tartans, the Vestiarium Scoticum, published in 1842. It was the work of two brothers, John Sobieski Stuart and Charles Edward Stuart. Born John Carter Allen and Charles Manning Allen in Wales, the brothers became prominent members of Scottish society in the 1820s with their claim that they were in fact descended from the Royal Stuart line, and their grandfather was Bonnie Prince Charlie himself. They subsequently changed their names and toured the country, taking advantage of their supposed royal connections.

They claimed to have papers of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s in their possession, some of which were a manuscript from the sixteenth century that detailed a number of old clan tartans from both the Highlands and Lowlands. No one ever saw the original and many people expressed doubts at its existence, including Sir Walter Scott who disputed the assertion that Lowlanders had ever even worn tartans or plaids of any kind in the sixteenth century. James D. Scarlett, an authority on tartan weaving, noted that “most of the Vestiarium tartans have clearly been designed on a drawing board rather than a loom“.

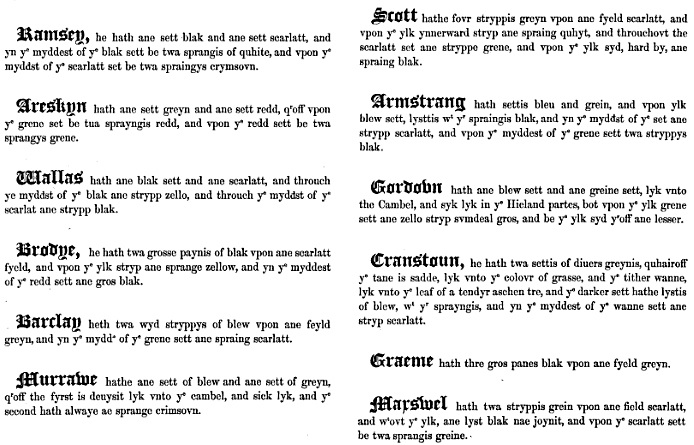

Despite their detractors, the brothers published the Vestiarium Scoticum in 1842. It contained written descriptions of seventy-three tartans, which were often vague and left open to interpretation. Each description was connected to a clan surname and accompanied by a colour illustration.

The book quickly became a best-seller, its publication perfectly timed to take advantage of the Victorian love affair with all things Scottish. It was snapped up by aristocrats who were desperate to have a tartan matched to their family’s history, and by weavers and tailors, who were taking advantage of the tartan boom.

An example of the text in the Vestiarium Scoticum

The authenticity of the Vestiarium was called into question on a few occasions, most notably by the Glasgow Herald, which published a series of articles titled The Vestiarium Scoticum, Is It A Forgery? in 1895, but it wasn’t until the publication of D.C. Stewart and J.C. Thompson’s Scotland’s Forged Tartans in 1980 that it was proved beyond any doubt that The Vestiarium Scoticum was a monumental hoax.

“Despite the misgivings of a few, but potent, authorities, these tartans were eagerly accepted by a public desperate to wear its ‘authentic’ clan tartans and a trade equally desperate to sell them, and they have remained with us, highly respected and totally unauthenticated. Beyond all doubt, the Vestiarium and its background material are complete forgeries.”

Regardless of their historical authenticity, the tartans documented in the Vestiarium Scoticum were adopted by the clans of Scotland and remain strongly associated with them today. In almost every case, particularly for Lowland families, the tartan design assigned to their name was being revealed for the first time.

Although the Stuart brothers gave no evidence of any pattern’s history and essentially pulled them out of thin air, the vast majority of these tartans are still in use by many of the families, and it is now accepted that the authenticity or legitimacy of a tartan doesn’t rely on the who, when, or how it was created, but on the approval of a clan chief and the acceptance and use of the tartan by the clan itself.

Hannah Givens says:

Love your theme! Some fascinating history here as well. I’ve got two Scottish clans somewhere in my ancestry, but no idea what their patterns were. Someone in my family knows. 🙂

April 25, 2015 — 8:06 pm

Fee says:

Thanks Hannah! You should definitely find out what your family tartan is, and wear it with pride 🙂

April 26, 2015 — 7:19 pm

Liz Smith says:

You should come and work at the Clan Desk!

April 25, 2015 — 8:36 pm

Fee says:

Haha! I’d love to Liz, maybe we could do a wee swap one day! 😀

April 26, 2015 — 7:20 pm

Samantha Mozart says:

Fascinating history, Fee. I thought these tartans dated back centuries, through clans.

Thank you!

Samantha Mozart

http://thescheherazadechronicles.org

April 25, 2015 — 9:53 pm

Fee says:

Thanks Samantha! 🙂

April 26, 2015 — 7:20 pm

Rosanne Martine-Braslow says:

oh my goodness… I must share your blog with my friend Lisette… everyone here is gaga over Outlander and your blog is amazing…

April 25, 2015 — 10:00 pm

Fee says:

Thanks so much Rosanne 🙂

April 26, 2015 — 7:20 pm

Sara C. Snider says:

Wow, how fascinating. Hoax accepted! 😉

April 26, 2015 — 3:05 pm

Fee says:

Possibly the most successful fraud in history 😀

April 26, 2015 — 7:21 pm

susiemac says:

Very interesting article. Has me wondering what other traditional things to which many people hold so dear began because of the scheme for more money.

Take 25 to Hollister

The View from the Top of the Ladder

April 26, 2015 — 5:27 pm

Fee says:

I think if you look far enough back in the history of any tradition you’ll always find the point where it was invented. Thanks for stopping by 🙂

April 26, 2015 — 7:22 pm

Pat Garcia says:

Hi,

I must come back and read this again. It is as if I am reading about some of my own history that was lost. Much of what you have written here resonates with my soul.

Thank you.

Shalom,

Pat

April 26, 2015 — 7:02 pm

Fee says:

Please do, Pat, you’re always welcome. Thanks so much for your kind comments 🙂

April 26, 2015 — 7:23 pm

Tarkabarka says:

Fascinating! All I knew about clan tartan history so far was that they are not as old as people think they are… I learned a lot from this post! 🙂 I have been to Celtic festivals in the US where people could go to a booth with their ancestors’ family names and look at patterns… it was kind of fun 😀 Then again Americans are ALL about Celtic heritage.

@TarkabarkaHolgy from

Multicolored Diary – Epics from A to Z

MopDog – 26 Ways to Die in Medieval Hungary

April 27, 2015 — 2:33 pm

JazzFeathers says:

Fantastic post. I knew already that tartans aren’t authentinc, but this post gives so much details. Loved it 🙂

May 2, 2015 — 7:33 pm

Mee Magnum says:

Though the #A2ZChallenge completed a few days ago, I’m still discovering new blogs as I work my way down the list. I’m glad I found yours! Very impressive blog! I’m going to have to read more of your articles now!!

–Mee (The Chinese Quest)

May 6, 2015 — 2:43 am

Shawn Griffith says:

Wow! very informative and interesting article. Who knew cloth and weaving could be interesting 😉

May 28, 2015 — 1:08 pm